Treatment-free beekeeping

On november 12, 2022, the 4th Annual Conference on resistance to the varroa mite was held in Hallsberg. The goal for us participating in these conferences is to be able to conduct a more trouble-free beekeeping without chemicals and with healthier bees.

Treatment-free lecturers

This year, Terje Reinertsen from Norway participated. He has almost 30 years of experience in treatment-free beekeeping. Melissa Oddie conducts research on Terje’s bees and bees in close connection with these. She is scheduled for next year.

Per Ideström, with 9 years of treatment-free beekeeping, and Magnus Kranshammar, with 7, shared their beekeeping experience. Some of us in Hallsberg have been completely free of treatment for a number of years. The others are well on their way. The number of participants at our annual resistance conferences has increased every year. This time we were more than 50.

A year earlier, on October 23, 2021, we had the 3rd Annual resistance conference in Hallsberg. Then we had Juhani Lundén here from Finland who told us about his path to treatment-free bees. He had for several years tried to reduce the amount of miticide, oxalic acid drip, every year. But it always ended after a number of years with the death of most of the bee bee colonies. So he got tired of doing it that way and stopped using miticides altogether. It was 2008. There were 15 survivors out of many more. Now he has about 50 bee colonies.

In Hallsberg, we have produced completely treatment-free bees after reducing the amount of the miticide thymol, successively for several years.

At the Annual Resistance Conference 8 March 2020, Annelie Bosdotter from Annelund (Eskilstuna) in Swweden gave a lecture about her treatment-free beekeeping since then 10 years. You can read about her (if you can read Swedish) in Bitidningen No. 6, 2021, pages 26-27. She could not attend this year but informed us that the bees are as healthy and prosperous as in previous years, now with 12 years of treatment freedom. The first resistance conference, which was aimed not only at beekeepers with ties to the Buckfast Committee in the Örebro District, was held on 8 dec 2018 (Bitidningen nr 3, 2020, pages 4-5)

Hallsberg

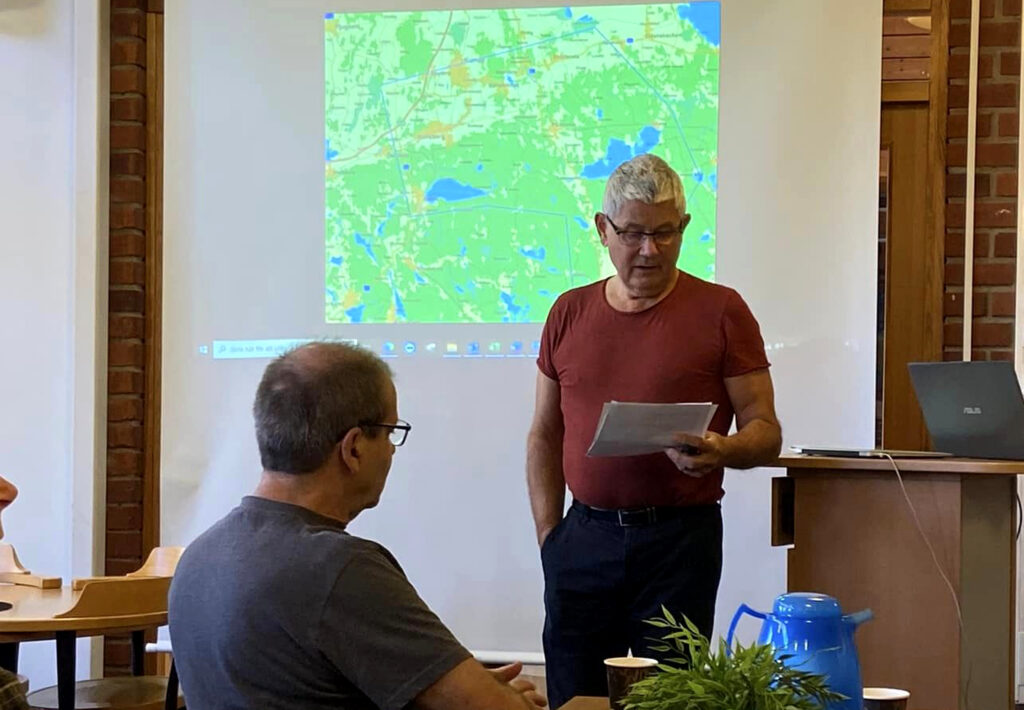

Peter Tesell, chairman in our local bee association, showed a map of the distribution of our resistant bees in the Hallsberg area that we call Elgon bees. Breeding work with this bee began in 1989 aiming at a combination between the East African mountain bee Monticola and the Buckfast Bee – https://elgon.es/beekeeping.html

The combination gave a large genetic variation that selection could work well out of. Already at the beginning working with this combination, the bees had greater resistance than we were then aware of. This has become clearer as the years have given us more experiences. From the year 2000 (after about 10 years), breeding work began to take place on 4.9 mm cell size.

There are just over 650 bee colonies in the Hallsberg area with about 10 beekeepers. The area of the bees is about 20 x 15 km (12 x 9 miles) large. 4 beekeepers have their bees completely treatment free. The rest of the beekeepers have treated on average about 20% of their bee colonies, but only with 5-10 gr (0.20-0.35 ounce) thymol(1-2 thin cellulose cloth pads with 5 gr thymol per piece) and nothing else, not even drone brood removal. The full dose of thymol in our area, with elgonbin has been / is 20 gr (2 x 2pcs 5gr pads) per year. The full dose for bees not selected at all is estimated to be up to about 40 gr per year.

Per Ideström

Per Ideström, former member of SBR’s Board of directors and at that time its representative in EU work, has for many years been passionate about varroa-resistant and treatment free bees. He has fought for breeding bees in that direction and faced incomprehension to invest a lot of power and money to the extent that he deemed desirable and necessary. He gave vent to his disappointment that the research has done so little for beekeeping in this regard, despite working with a bee population (Gotland bees) that has been said to be resistant for many years.

He was one of the three who carried out a literature study on behalf of the Swedish Beekeeping Association (SBR) with the help of funds from the Swedish Agency for Agriculture’s National Program. This literature study involved work carried out in different parts of the world to select a varroa-resistant bee: Introduction to breeding Varroa resistant bees, Final report (2004) http://www.lapalmamiel.com/a/study.pdf

Per Ideström translated about 20 years ago from the American Bee Journal an important pioneering selection work for varroa-resistant bees carried out by Eric Erickson at the Carl Hayden Bee Research Center. Tucson. AZ: https://www.elgon.es/diary/?p=457

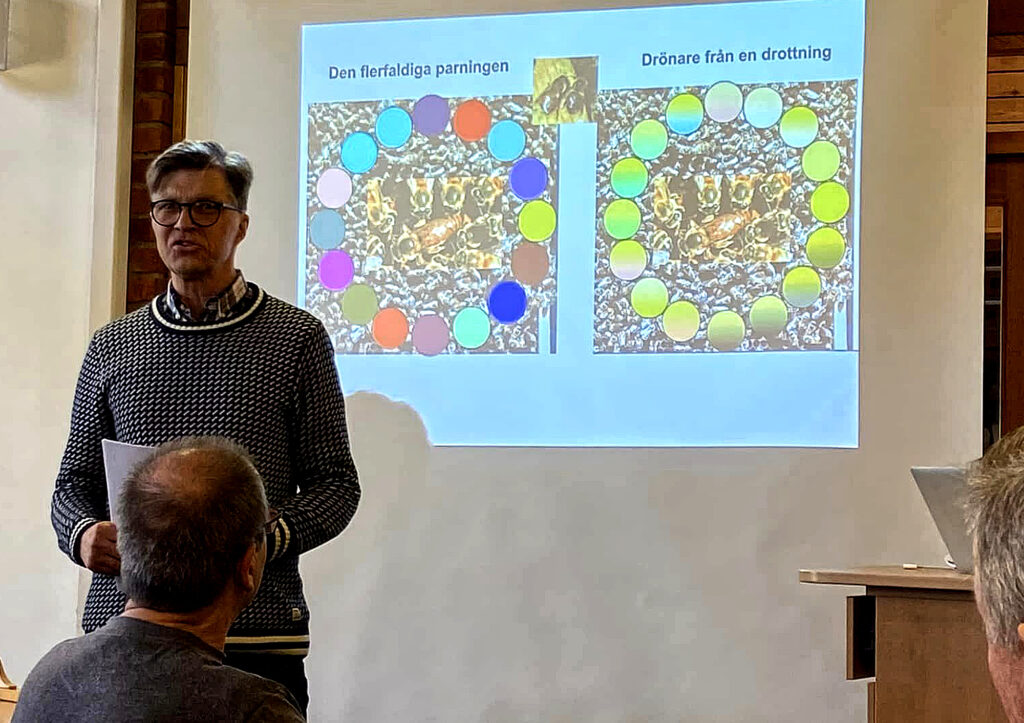

Ideström pointed out in his talk the queen bee’s multiple mating, i.e. that she naturally mates with an average of 20 drones. It is of importance that the drone seed in the honeybee queen provides a sufficiently large genetic variation. The offspring become sister groups with different fathers who, due to their genetic variation, can better take care of different tasks, for example making life miserable for varraok mites. This provides a strong potential for the selection and adaptation sought, either through natural or beekeeper selection, resulting in the survival and thriving of the most adapted bee colonies

Ideström mentioned that for several years he has had 7 bee colonies located in a rather isolated and upland forest area in central western Sweden. A draught-poor area. No queens have been bought and exchanged by him sice the establishement of the apiary. The origin of the small population is Elgon bees (https://elgon.es/beekeeping.html) and some swarms of unknown origin. He uses 4.9 mm cellsize. It is now the 9th year without treatment of any kind against the varroa mite. Last years without any winter losses. No DWV bees (Deformed Wing Virus bees) have in recent years been seen in or outside the colonies. Splits are made from the best colonies. They replace the worst. The honey harvest this year was a total of 90 kg (200 lb). An equal amount of honey was left for winter in the colonies and an additional approximately equal amount of sugar was given for winter food in early autumn.

Terje Reinertsen

Terje Reinertsen’s beekeeping, located about 20 minutes north of Oslo, has attracted attention in recent years. The reason is his varroa-resistant bees. They have not been exposed to varroa chemicals for almost 30 years. In 2019 I visited him and it resulted in articles in Bee Culture (https://www.beeculture.com/varroa-resistant-bees-get-1-million-in-norway/ ), in Swedish Bitidningen (Bitidningen no 12, 2019, pages 8-11) and in Swedish Gadden (Gadden no 1, 2020, pages 4-7). He also ended up on my blogs (https://naturligbiodling.eu/blogg/?p=578224 and https://www.elgon.es/diary/?p=416587 ).

On 22 February 2020, he gave a lecture at the Apiscandia conference in Sunne, Sweden (Bitidningen nr 4 2020, pages 4-5). This year, 2022, it was time to visit us in Hallsberg.

Terje shared how resistant bees differ in behavior, once they have established themselves as resistant, compared to when they are regularly treated by chemicals against the varroa mite. I will return to this later in this article.

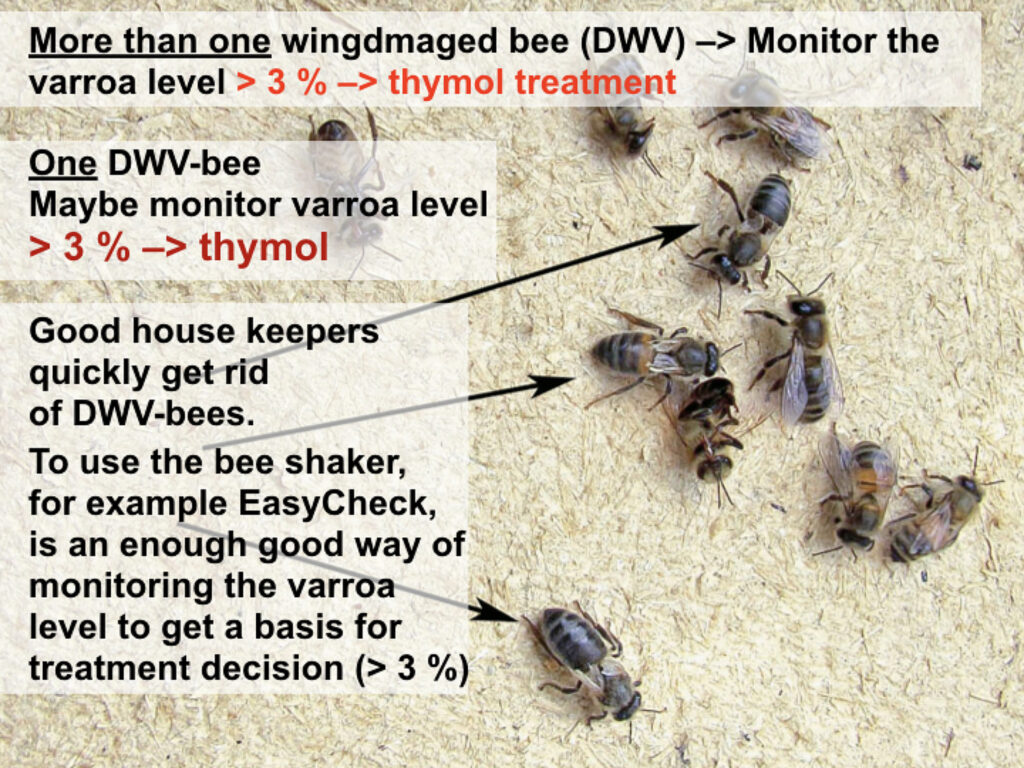

When the bees are treated every year, it is important to keep track of the varroa level, or the infestation rate (in%, IE mites per hundred bees).

Resistant bees have developed hunting properties, they hunt mites in several different ways, in capped brood and on the bees. Terje says that this, at least in part, is something they have developed through response to movements and pheromones of the mites and also learned from other bees.

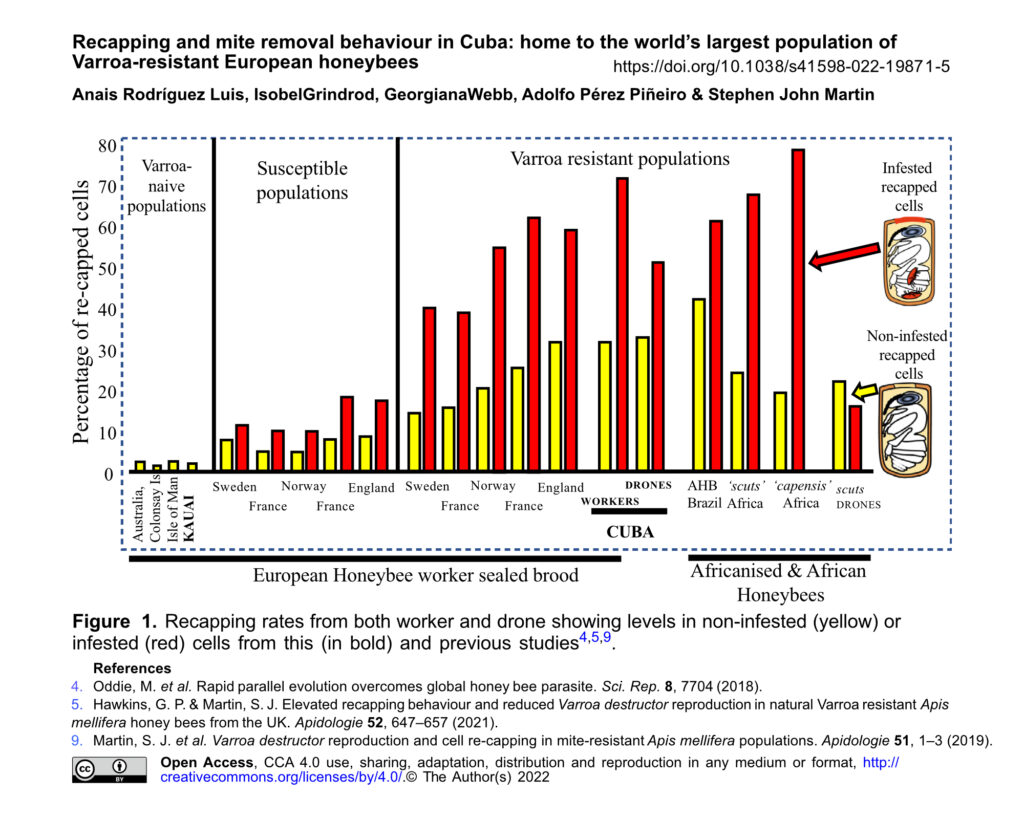

One such hunting characteristic is what is known as recapping. Bees identify capped brood cells in which there are varroa mites, open these capped brood cells, and then recapping the bee pupae. Unlike VSH, the miteinfested brood cells are not cleared out, but fully grown bees eventually hatch. The mite is disturbed in its reproduction and its life span is shortened. Bees sometimes make mistaks and uncap and recap capped brood cells where there are no varroa. Dr Melissa Oddie documented the recapping behaviour with Terje Reinertsen’s bees in her doctoral thesis.

Recapping incidence in other resistant bee stocks have been investigated and found. The result in such an investigation is published in a scientific report by Nature (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19871-5 ). it seems that the more resistant a bee strain is, the more prevalent is recapping. It also occurs in non-resistant bee colonies, but to an insufficient extent.

Recapping is not the only hunting trait of resistant bees. Purging of pupae invaded by mites (with offspring, and mite invaded pupae without offspring also occurs). VSH can be effective, the bees identify the presence of varroa mites in capped brood, mites that have offspring, and purge such bee pupae. Dr Oddie did not find in her investigations that VSH was present in Terje’s bees. Thus it could not the explanation for their resistance.

.

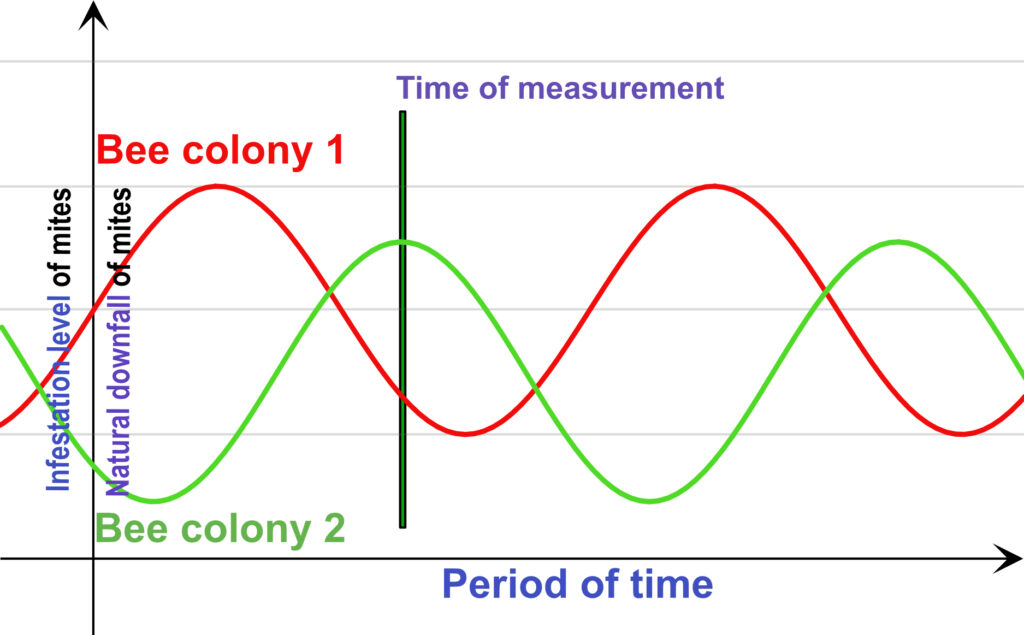

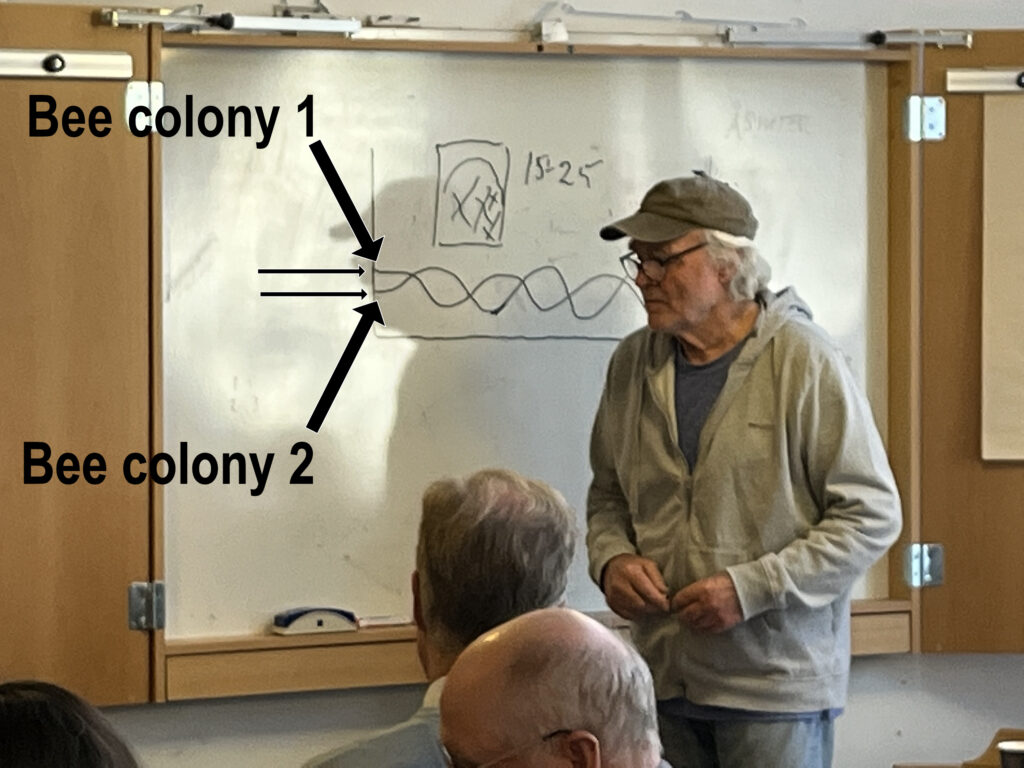

Terje Reinertsen described how the varroa level in resistant bee colonies varied somewhat with the resemblance of a sine curve , similar to that shown by alternating current. You could not expect that the sine curves of different colonies vary in phase so that the different peak levels (or the minimum levels) of mites occur at the same time. And you could not expect that he sine curve intervall is the same between the peaks. When the amount of mites was at its lowest in one colony, it could maybe be at its highest in another colony (or almost). And at one moment, the amount of mites in the less good colony could be lower than in the better. In resistant bees, it is therefore not possible to compare the infestation rates/varroa levels of different colonies at the same sampling time. Perhaps an examination of the average daily natural downfall of mites in resistant bee communities over a longer period can provide figures that are comparable enough good.

However, be sure that although the maximum varroa level differ between resistant colonies, they are all resistant. Surviving and thriving colonies are proof of this. Resistant here means that the presence of varroa mites in the colonies does not significantly affect how well the bee colony functions , without interventions from beekeepers.

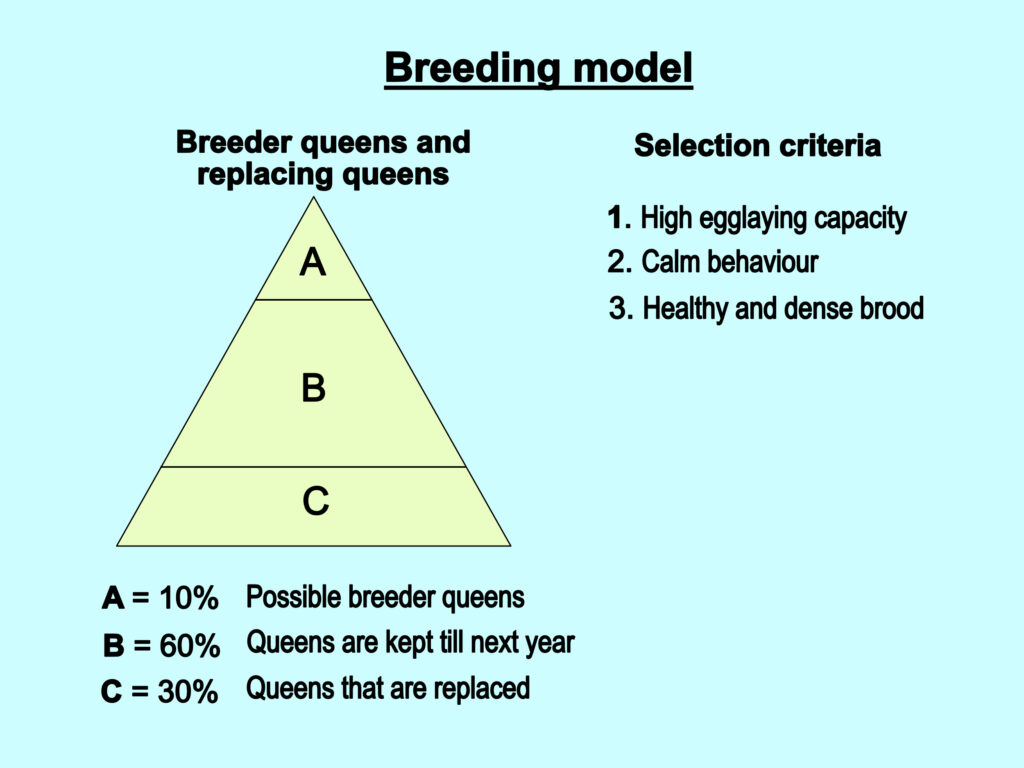

This means that selecting for low varroa infestation in a population of bee colonies that have not been treated against varroa for a number of years (perhaps at least three years) do not give values that can be used to rank the colonies. Terje indicated three traits that he found meaningful to use as selection criteria in his selection:

1. High egg-laying ability

2. Calm behaviour

3. Healthy and tight brood

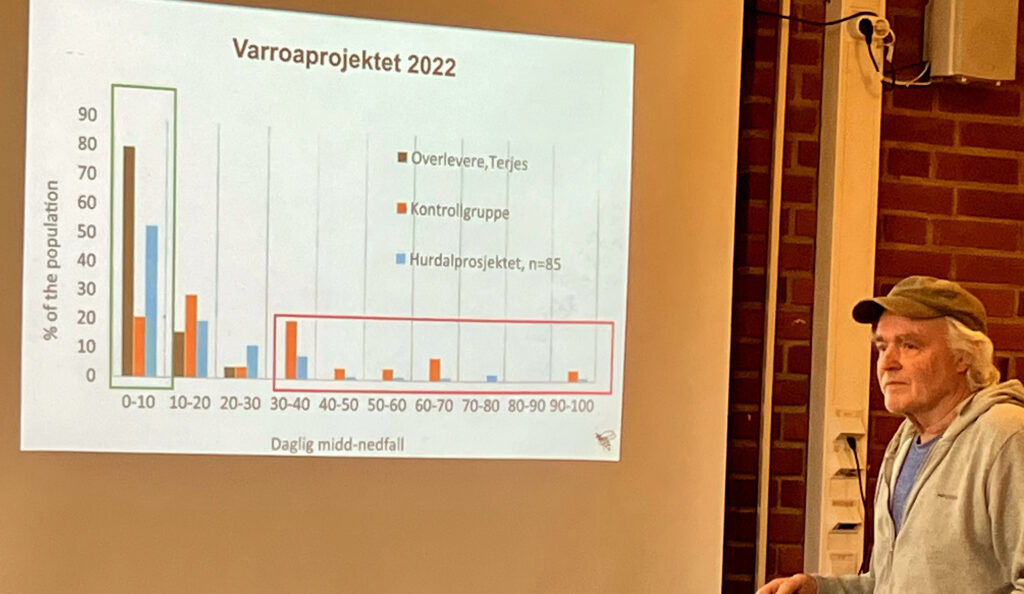

In the research that is underway today at Terje, the average daily natural downfall of mites over a longer period of time has been measured. Three groups have been investigated. Terje’s bees, another bee population bred for resistance without miticides for just over 10 years, and a control group with susceptible colonies. The latter colonies were placed in the same apiary as Terje’s bees. A summary of this survey has been published in the Norwegian beekeeping magazine (Birøkteren ,No 8, 2022, P.28). Terje’s bees had much lower daily downfall than the other bees, especially the control group. No colonies were treated during the survey, not even the control.

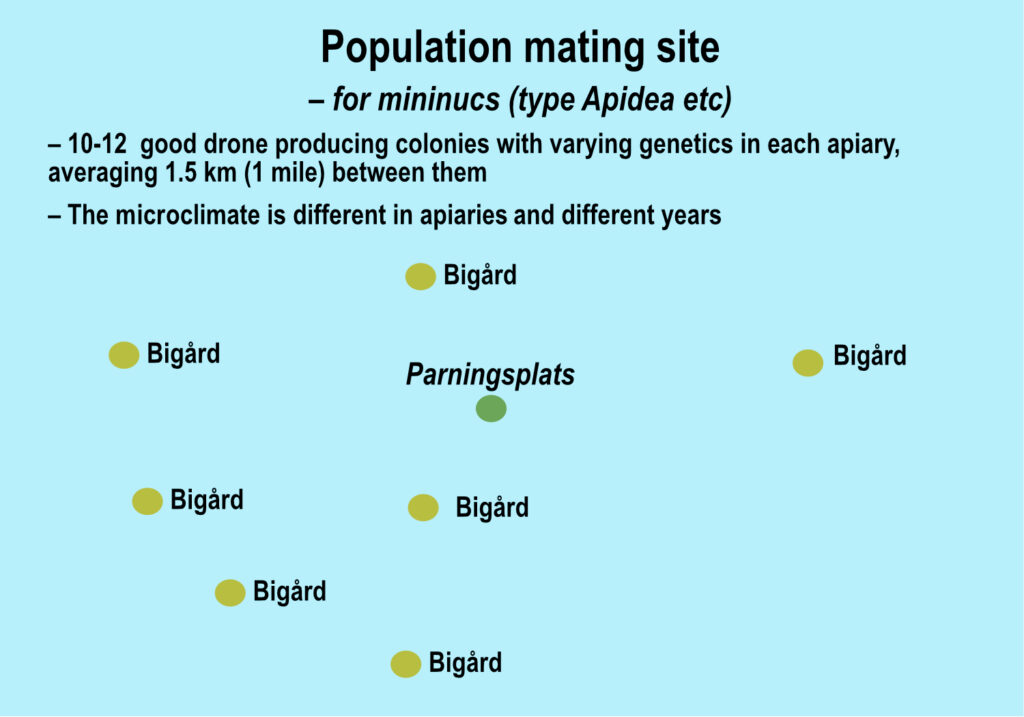

Reinertsen use so-called population mating for their virgin queens. He has set up a mating site for this purpose. Several apiaries are located around this site. The furthest one is 3 km away. To the nearest one it is a few hundred meters. It is a much greater distance to non-Terje bees. He has at least 10 bee colonies in each apiary, good quality colonies with different kinds of kinship between each other to contribute to as wide a genetic set up as possible. Drones from his apiaries around the mating site are estimated to be the only ones that can mate with the virgin queens. However, he says that it’s enough with 75% good drones present in the mating area, to make it possible to develop a still better bee strain. Terje uses 4.9 mm cellsize. Winter losses are low. Honey crops are high.

.

Johan Ingjald

The bees of Johan Ingjald are placed in the eastern part of Hallsberg, with about 100 bee colonies. He has been focused on treatment-free bees since varroa struck in 2007-08. He has tested ideas and different types of hives, such as topbar- and Warré hives, and learned a lot. He ended up with a 12- frame square shallow (half jumbo dadant) hive that some of us use, but a few of the topbar- and Warré hives remain. Different races have passed the revue. Some mixed A. m. mellifera remain, but Elgon bees have met his requirements best. He wintered 90 square shallows, 10 topbar hives and a few Warré hives the autumn of 2022. He uses 4.9 mm cellsize.

He treated varroa in different ways during the early years of mites. But the losses were far too big. Winter survival became much better with thymol pads for varroa treatment (see https://elgon.se/tymol.html). In 2017 he began monitoring the varroa level using 1 dl of bees, from combs close to the brood but not from brood frames, to avoid including the queen in the shaker (https://elgon.es/varroalevel.html). Below 3 % infestation level colonies were not treated.

He kept track of virus by carefully looking at a hard board in front of the entrance at intervals of one week/10 days. He soon learned that it was before noon that the bees ”cleaned out with the garbage” from the hive, throwing out any virus-sick bees, for example DWV-bees (Deformed Wing Virus). If there are no DWV bees in the afternoon but sometimes a few in the morning, there is a good prospect that the bee colony will cope with the virus and survive well, especially if the colony has been treatment free for some years.

In 2021, he did not treat any colonies against the varroa mite. He also did not monitor any varroa level. On the other hand, he kept a close eye on possible virus effects on the bees by studying the hard board in front of the hives concerning eventual wing-damaged bees and possibly seemingly normal gray bees (young bees) that crawled around in front of the hive, but could not fly. He has realized that it is in first place not the amount of mites that is decisive for the survival of a colony, but eventual virus effects and virus resistance in the bee colony.

The winterlosses 2021-22 was only 5%, the lowest since varroa made beekeeping difficult.

Strong enough colonies but still not up to an acceptable standard, he divides into splits, so drones from their substandard queens are minimized. The splits and other poorer colonies receive mature queen cells or new mated queens bred from colonies that have fared well and are without virus symptoms. Such colonies could sometimes have a varroa level that with more susceptible colonies would have been assessed as too high, but here without it being noticeable on the state of health or performance.

Radim Gavlovsky

Radim Gavlovsky has a couple of hundred bee colonies scattered in the municipality of Hallsberg. Mostly haives with 10 frames medium Langstroth (448 x 159 mm). The rest Swedish standard (366 x 222 mm), called LN. He started as a beekeeper with some Elgon colonies. He greatly expanded his beekeeping the following year, collaborated with the rest of us in the Elgon area and got good queens cheap to work with. This helped fill the airspace with good drones for all our queens.

He partly goes his own way. It’s exciting. Despite our advice to the contrary, he has as many as about 60 bee colonies in one apiary (a rich nectar yielding area). The other apiaries usually have 6-8 colonies. He uses 4.9 mm cellsize in at least half of the combs in a box, placed in the center. The other combs are drawn without foundation.

In his early years he made a small straw skep, only 20 liter’s (42 pint) volume. He gave it a small early swarm. The skep has survived for 8 years without more than sometimes a few kg of extra honey for feed and without varroa treatment at all. It has been starvation that has been the biggest threat, the volume is probably too small for a good amount of stored feed. The small colony gave up last spring. But Radim has learned a lot, for example that when the bees had filled it in July with honey, the bees took a vacation from brooding the rest of the season, except for a short brood season late in the season. The bees threw out mites and occasional DWV-bees during the summer. The harvest was made up of a swarm every year, except one year, when the colony replaced the queen without swarming.

He has hoping to reduce the number of colonies for a couple of years now, but has so far failed and instead increased the number every year. As he increased the number of colonies rapidly in his beginning years, he then never had enough of boxes, drawn combs, frames with wax foundation or just empty frames. He therefore received more swarms than he otherwise would, and he learned to appreciate swarms.

The bees built a lot of drone comb and he got to see what the bees were doing with so many drones in the colonies. After all, he did not practise drone brood removal as a varroa control method. The bees did this themselves, thus saving the worker brood from varroa mites. When the colony had enough of many drones and a lot of mites, both parts were thrown out of the hive by the bees.

When he started as a beekeeper, he used thymol pads (smaller but similar to Thymovar) against varroa. Home mad pads are described here: https://elgon.es/gradualresistance.html. He usually used two 5 gr-pieces twice with 10 days in between in late summer. Now 2/3 of the colonies get no treatment and 1/3 get a smaller amount (one or two 5 gr pads once). Many of these treated actually get only 1 or 2 pads for only 1 or 2 days. It stimulates the bees ‘ own cleansing activity, he says, in addition to knock down some mites. One should not treat too late in the season, he says, if thymol is used.

Bees that get access to a good amount of good quality pollen and nectar find it easier to stay healthy.

Don’t disturb the bees unnecessarily, he points out. Radim’s bees get mostly honey for winter feed, middle and late summer honey, sometimes only heather honey, which is a challenge. Then they take every opportunity during the winter/spring to cleansing flights. Plus additional sugar for those who need to be supplemented. Winter losses are 2-3 %.

A good piece of advice from Radim: overwinter small splits with new queens, they are useful in different ways. They can be wintered, 2-4 splits in one box, and on top of a strong colony.

Magnus Kranshammar

Magnus Kranshammar described his and Ulrika Kranshammar’s committed journey into the world of beekeeping and varroa-resistant bees in a local bee club in the south west of Sweden. Since 7 years, their bees are treatment-free.

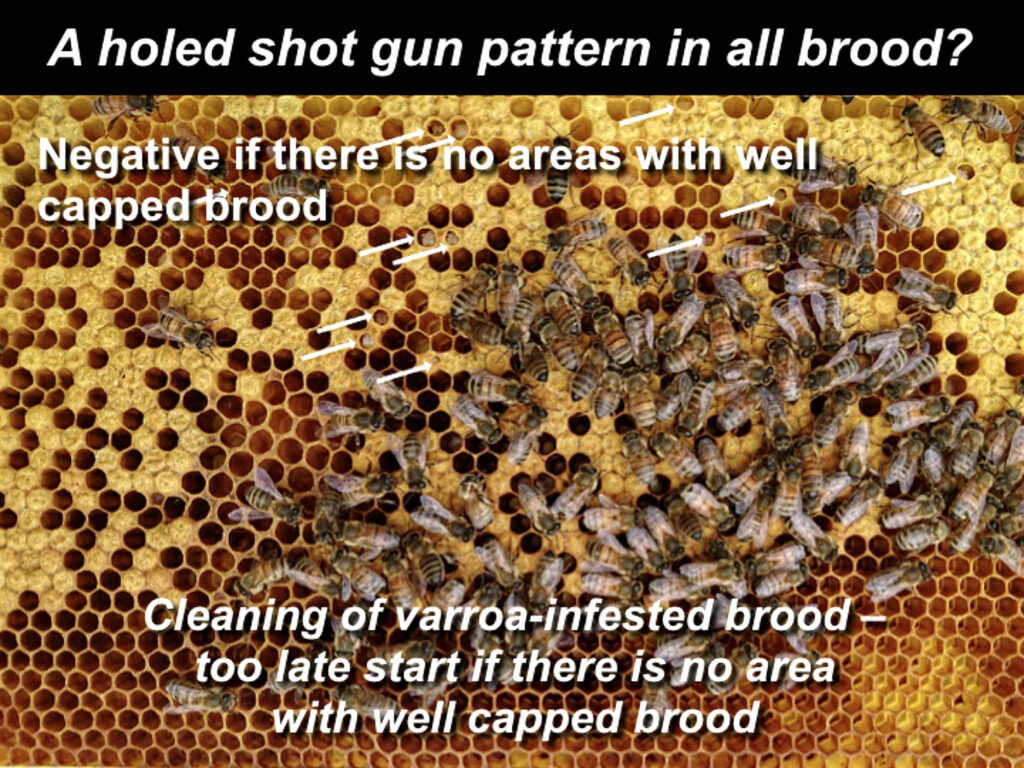

A fundamental part in working with the bees is not to disturb them more than necessary. He keeps track of the state of health with the help of a hard board in front of the entrance to quickly observe what the bees may have dragged out of the hive – sick bees, bee pupae, etc. Early on, colonies were monitored for varroa level. The beeshaker jar was used (https://elgon.es/varroalevel.html). Now colonies are checked that show signs that everything may not be right, e.g. poor development or discarded pupae, shotgun brood pattern, etc.

Jranshammar do not focus on making big honey crops. They still harvest good crops. But the amount of honey can differ a lot between different apiaries. The surroundings of an apiary and the weather matter a lot. The winter stores consists about 50% honey. Winter losses are lower than the national average, 10-15 %.

Magnus picks up swarms. Many come from other people’s bees that are not treatment free. All of these swarms do not make survive, but some do. Maybe some bees from his treatment-free hives drift into them, and teach their new friends to hunt mites?

Kranshammar has also developed slightly different variants of so-called longhives, with entrances at both the short ends. The oldest frame size in Sweden, and still in use is the same as one of the old American frame sizes (300 x 300 mm – 12” x 12”) It works well in a longhive and Kranshammar uses this in their longhives. You can avoid heavy lifting. Honey combs can be harvested from one or both ends of the longhive.

A detail that helps the bees to stay protected against possible robber bees is a small entrance. A round 30 mm hole a bit up from the bottom works well. Kranshammar uses such entrances on their longhives. The small entrance does not prevent the bees from collecting good crops. In these hives they use 5.2 mm cell size. In addition to long hives, they also have colonies on 12-frame square shallow langstroth boxes. Here they use 4.9 mm cellsize.

Magnus and Ulrika greatly appreciate the contact they have with Kirk Webster from Vermont, a treatment-free beekeeper for many years. Kirk was a speaker at the Resistance Conference in Varberg a few years ago. This year he visited Terje Reinertsen in Norway. He made his way past Erik Österlund on the way home to Kranshammars. There he became a good inspiration for 10-year-old Tilia, who is an active and interested beekeeper, neighbor of Kranshammar. In America, beekeeping has growing problems with neonicotinoids, a type of synthetic crop protection chemicals. Treatment-free bees, like other bees, can have major survival problems from these chemicals. The Neonics chemicals poison the pollen that the bees collect to feed their brood. In Europe, many of these chemicals are banned.

At the end of his talk, Magnus presented an initiative he and Ulrika have taken, an association to:

* Promote treatment-free beekeeping

* Provide labeling for honey from treatment free bees

* Give the consumer the opportunity to choose such honey

Erik Österlund

Erik Österlund talked about his experiences and important details in the development of treatment free bees. To reach this goal, a restored microbiome is required to achieve as carefree beekeeping as possible with healthy and strong bee colonies. Today he has about 90 bee colonies in several apiaries in the Elgon area in Hallsberg. He uses 4.9 mm cellsize.

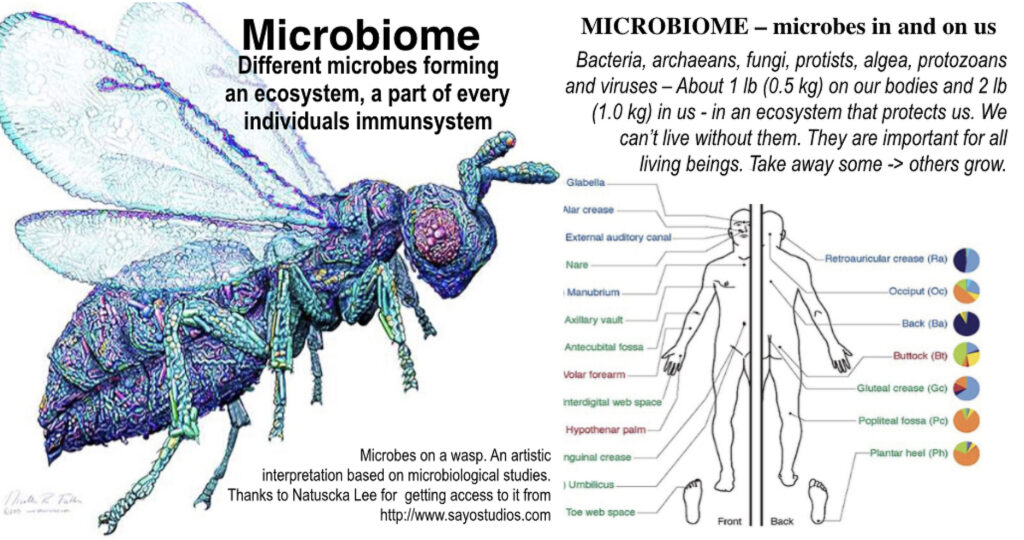

What is called microbiome is a mixture of microbes in balance with each other, bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc. All living beings live in a kind of sea of microbes. Without them, we can not live. The microbiome, an adapted balance of different microbes is indispensable for the immune system. A human microbiome weighs just over 2 kg. It is on us and biggest part in us. Think of what happens in our stomach when we need to take antibiotics.

Restoring a microbiome into balance requires that bee colonies are managed so that virus levels can drop to a level where the other microbes can recover and help the bees and the immune system to hold back high levels of viruses. An internet search on “microbiome honeybees” gives a lot of reading, among other things: https://theconversation.com/bees-seeking-bacteria-how-bees-find-their-microbiome-129534.

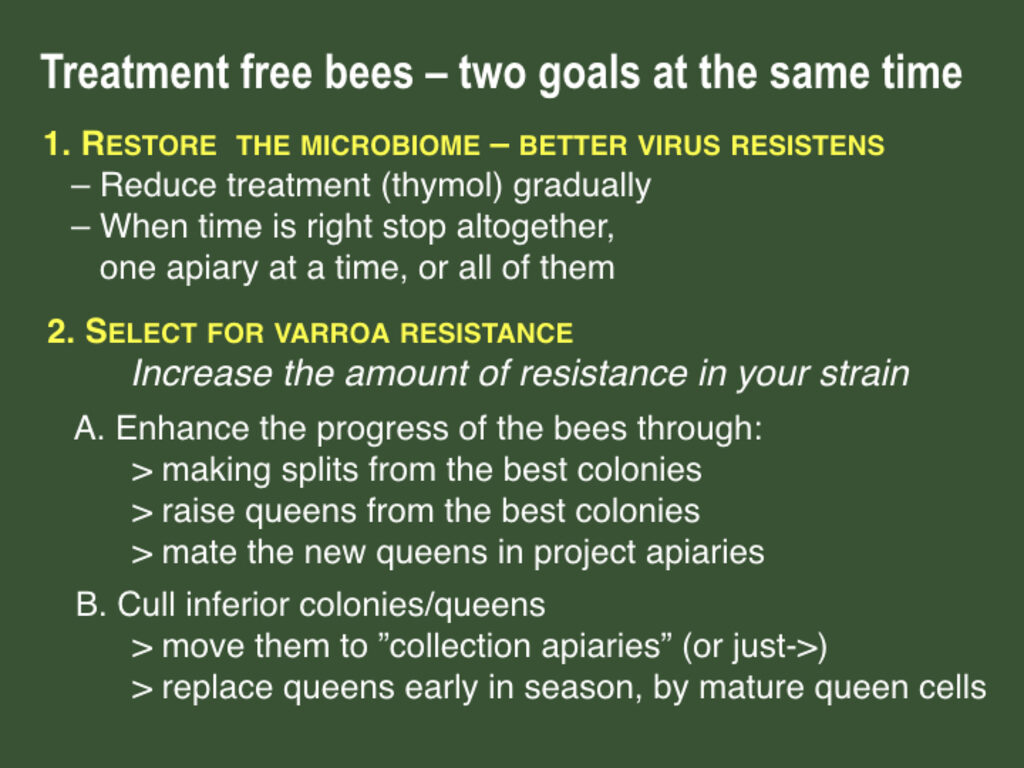

The management should give room for decreasing the use of organic and synthetic chemicals. Eventually it will be possible to stop using them completely.

Virus levels can drop sufficiently in two different ways.

1 – no treatment at all

2 – gradually decreased treatment

– 1. A number of bee colonies, with more easily defensible small entrances) are placed in a reasonably isolated apiary, at least 2 km other bees. It ensures that these bees’ exposure to re-invasion by mites is minimized. Preferably 3-5 km distance to other bees for a greater chance of getting all matings there with at least 75% right kind of drones, 15 of the 20 drones that a queen is mated to. Then there is a great chance that the selection and development of resistance will be progressive. Every year the inferior queens are replaced. Provided that at least a few survive that is enough to continue the work.

Some colonies with better virus resistance may be able to cope with the eventual domino effect that may occur when other colonies in the apiary crash. Survivors are likely to hunt mites a little better and do even better when the susceptible colonies are gone. This path to treatment free bees gives a big risk to lose a big part of the bee colonies involved, especially if you start with many colonies in such an apiary. This risk will decrease rapidly in the coming years. The more isolated the apiary is, the better the results. New queens are mated in such an apiary.

If you start such an apiary with splits and full size colonies with healthy bees (no DWV-bees observed) and new laying queens from a reasonably resistant stock of bees, the chance is good that none or just a few colonies will be lost because of too high virus levels.

– 2. A number of bee colonies are placed in one or more reasonably isolated apiaries in close proximity to each other. There they are managed as we have been doing in Hallsberg. https://elgon.es – > gradual resistance. Check the degree of infestation of varroa regularly. Over 3 % (9 mites per 1 dl of bees from combs close to brood but without brood. If needed treat with thymol pads (https://elgon.es/gradualresistance.html).

New queens are mated in the most isolated of a “project” apiary. The queens that are placed in project beehives are bred from the best colonies in those apiaries.

As the interval between treatments are getting longer and longer, it’s probably a sign that the bees are hunting mites better. You also keep track of the presence of possibly wing-damaged bees by reading the hard board (0.5 x 0.5m, 20” x 20”) in front of the entrance. Any change in resistance to viruses can be understood from what is seen on the board. And the microbiome recovers better the fewer treatments it gets in a year. When the thymol treatment has dropped to 5-10 gr in a year, it seems that the microbiome has recovered so much that you can seriously think about whether it is time to stop the treatments completely, especially if you are down to 5 gr/year. One can begin and stop treatments in one apiary with few number of colonies.

At the beginning of the road to treatment-free apiaries

1. Measure the varroa level-2-3 (or more) times per season – ” good enough basis for decision” (when there is a normal amount of brood in the colony) – treat no later than one week after a measurement shows that it’s needed. We have only experience of success when using thymol pads like this.

2. Use a hard board 0.5 x0. 5 m in front of the entrance. Inspect what the bees have cleaned out every 7-10 days – and get an impression of the ”virus level”

3. Is the bee colony developing as expected?

4 A. Are there at least some areas with densely capped brood?

4 B. You shouldn’t find only capped brood areas that have about 50% holes in which capped brood had been expected, like a shot gun pattern.

.

When almost completely treatment-free apiaries

1. Use a hard board 0.5 x 0. 5m in front of the entrance. Inspect what the bees have cleaned out every 7-10 days – check the ” virus level”

2. Are there areas with densely capped brood?

3. Is the colony developing as expected?

4. Measure (optional) the varroa level 1 (or more) times per season (when there is a normal amount of brood in the colony) – treat no later than a week after a measurement shows that it is needed

Completely treatment-free apiaries

1. Use a hard board 0.5 x 0. 5m in front of the entrance – check the ” virus level”

2. Is there areas with densely capped brood in the colony?

3. Is the colony developing as expected?

4. Measure the varroa level when there is a normal amount of brood in the colony, if point 1-3 above give reason for that.

To help the bee colony during the breeding work for better varroa resistance, it is recommended

1. At first, if possible, use few colonies in an apiary. Increase the number as varroa and virus resistance increases. With more hives you will increase good drone influence in the area.

2. Use a small entrance. (Bitidningen nr 1-2, 2020, pp. 10-13)

3. Use small natural cell sizes. https://elgon.es/helpingresistance.html

Hi Erik, Thanks for posting so much detail from the conference. There’s a lot of info here to digest. It’s great that you all are seeing so many positive results. In the states it is slower as we still have so many bees sold and moved all over the country, with very little emphasis on local adaptation. My bees are looking good with the use of organic acids. I’m trying to downsize to a more manageable number of around a hundred, so I can have time to monitor mite levels more closely, and select colonies to breed from. It has been difficult to downsize, much more work than expanding, but I’ve made good progress.

I’m looking forward visiting Hallsberg again in the future, hopefully in the next year or two. Look us up if you’re in the states.

Richard

Hi Richard,

Yes, it’s a lot of info. Took some time to write it down and fix pictures. But I wanted a correct report and a good amount of knowledge to share how we have worked so it hopefully will be easier for others to do the job. Itäs good the moore we spread the knowledge so it will be easier to hold what we’ve achieved.

You are welcome visiting. Thanks for invitation.

Erik

Hi Erik, thanks for the interesting stories of all kind of treatmentfree breeders. In 2016 I started with the conversion of my Buckfast beecolonies to 4,9 mm cells foundation and stopped at the same moment the mite treatments of this 4,9 colonies. In the years after 2016 I converted all my 80 colonies and stopped in 2019 all treatments. In 2016 I started also with incrossing of VSH traits and general hygienic behaviour.

My losses of the last three years were below 5%. Honey production is above average for the Netherlands.

This year I’ve got Elgon breeder queens with high VSH traits. They’ll be integrated in my breeding and selection programm.

Ben

Hi Ben

It’s good to know that the number of treatment free beekeepers here in Europe are increasing!

ERik

Terje: In resistant bees, it is therefore not possible to compare the infestation rates/varroa levels of different colonies at the same sampling time. Perhaps an examination of the average daily natural downfall of mites in resistant bee communities over a longer period can provide figures that are comparable enough good.

I did that for 5 years in Germany and that’s how it is. You can even find out if there are mite resistant colonies among formerly treated colonies and you can evaluate the impact of the environment or if the queens are still laying good. You can see whether the bees do a brood break , you can microscope the downfall for bitten mites and get much more information about what happens. No need to open up more than necessary.

Thanks for all the information! My head is spinning.

In Sweden my colonies from Erik so far all survived for 3 years ( they and Radim´s swarms lived 4 days ago), so I can be more relaxed. Bee research is wonderful!

Sibylle