Randy Oliver in Sweden 8 Dec 2013

Randy Oliver in Sweden 8 Dec 2013

7-8 December, Randy Oliver California USA, Steve Pernal Canada and Mark Goodwin New Zealand had a workshop on parasites and pathogens, mainly Varroa and American Foulbrood. Mark Goodwin with the help of video Skype. I only could participate on Dec 8. I overheard good teaching, mostly on handling AFB and breeding for Varroa resistance. I want to share somewhat of what Randy Oliver gave us, as I understood his teaching.

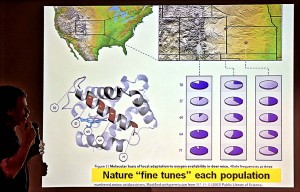

Locally adapted bees

Randy stressed the importance of locally adapted bees. Even if you happen to breed resistant bees, the queens people buy from you might not be resistant at their place. They may contribute in developing their bee stock, but probably adaption to the circumstances that form the new situation may take some generations.

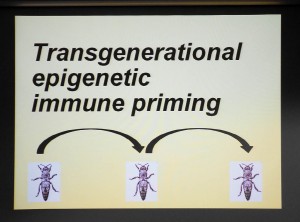

Epigenetics

Epigenetics is the first adaption process that takes place in respons to a changed situation – bees and queens moved to a different location with different nectar flows and climate – newly arrived pathogens and parasites – or new varieties of pests and parasites. The genetics at hand in the bees respond to the differently chemical environment that these changes create and causes their DNA to be read and be used differently by them to express a better use of resources and a better defense against enemies. These changes will be inherited to next generations and may well have to be settled during some generations for best effect. This is an adaption process.

Genetics

During this process selection also is taking place, mainly through culling of the least fit, those that can’t handle the new situation die – or you shift the queens in those colonies. And a changed variety of bees will be created with a different setup of gene varieties, alleles. This changed genepool of the population of colonies at this place will be adapted to the new situation. Another adaption process going on, hand in hand with the first one.

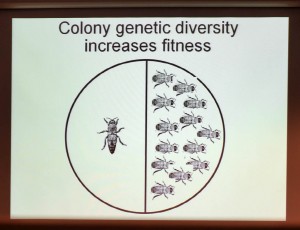

Genetic diversity in the bee colony

It’s not only one enemy or difficult situation the bees have to handle. And here is the genetically different sistergroups in e bee colony very useful. Not all bees have to be able to detect Varroa mites in broodcells and remove those pupae with fertile mites. It’s enough with maybe a couple sistergroups of workerbees. The other ones maybe needed for taking care of other things in first place.

Genetic diversity between bee colonies in the population

A sudden changes in climate can cause most colonies to die, un unusually hard winter or a long dry season. Those few surviving will be able to rebuild most of the genepool again – if the queens are mated to several drones, from many of the colonies in the locality where a group of colonies are forming a subpopulation of bee colonies. This is one of the reasons why queens rarely should be mated at a mating station where a few closely related colonies produce the drones for the virgin queens. For a sustainable stock of bees.

In a breeding program, to give the bees the best resources for both the immediate and the longterm adaption – genetic variation inside the bee colony is important, but also between the bee colonies. This gives the bee stock ability to keep a high variation in the colonies over the years.

Strategy

- Select for the best; but it may be even more important to cull the worst.

- Be sure to maintain genetic diversity if you are controlling the drone pool – breed from a large number of queens each year.

- Breeding from only a few queens can rapidly lead to inbreeding. If you only breed from a single queen one season, all the drones the next season would all share the same grandmother.

- If you only have a few hives, swap queens with other beekeepers in order to maintain genetic diversity.