It appears now and then articles in especially the German language stating that the enlarging of cellsize historically never have occurred, but instead what’s happened is going back to normal larger cellsize. And those decreasing cellsize is doing something unnatural. How come?

In the English language there are many sources from the 19th and 20th century leaving no doubt an enlarging have taken place. Wildman, Cowan, Root, Cheshire, Bee World in the 1930th, etc.

The icon Enoch Zander

One of the old German icons in beekeeping is Enoch Zander (1873-1957). His book “Die Zucht Der Biene” was first published in 1920. After his death new editions changed name to “Haltung und Zucht der Biene” because they were revised by Friedrich K Böttcher. It was published in its 12th edition in 1989. The book is a classic beekeeping book in Germany.

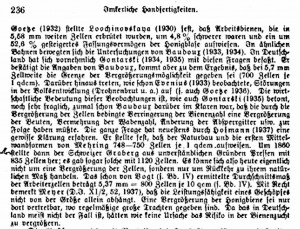

The picture shows a part of page 236 from the 5th edition from 1941. Click on the picture and enlarge it so you can read it easier. (If you can read German with these old letters.) To go back to this page click on the return button in your browser in the upper left corner. One passage here says translated into English:

“The whole question has recently been cleared somewhat by Hofmann (1937). He found that natural comb and the first foundation molds by Mehring had 748-750 cells/dm2 [≈5.55 mm]. Around 1860, Graberg from Switzerland , for strange reasons, produced molds with 835 cells [≈5.25 mm], there were even some with 1120 cells/dm2 [≈4.55 mm]. So today’s production of large cells is indeed no enlargement, but a reversion back to the natural.”

My calculations to mm translations are made with the formula

X=100÷√(A÷2.315)

where X=cellsize in mm and A=cells/dm2. Backcheck the formula with

A=23150÷X2

Earlier in the book there are some figures which contradict this statement. Cellsize figures given by a couple of Russian beekeepers, Tuenin and Bogdanov. In the 12th edition from 1989 they say that Tuenin in Tula (120 km south of Moscow) had measured cellsizes ranging between 4.99 mm and 5.26 mm. Bogdanov had in Leningrad measured 5.53 mm to 5.69 mm. (I’m not sure if these cellsizes are from comb with or without foundation. And if without if it’s from a colony whose bees are born in a colony with foundation of large cells. If for example the Leningrad figures come from a swarm from a colony on cellsize 5.4-5.7 it may well draw the given cellsizes the first time they are doing it without wax foundatin. Next generation will draw even smaller if given the chance.) The contradiction between these figures and the conclusion is even more clear if you also have the 5th edition to compare with. In this edition the Tuenin figures from Tula is given to be 4.74 mm to 5.00 mm. The revision in the 12th edition made the contradiction milder changing the figures a little (couldn’t do much harm could it?).

The influence of the classic book

The majority of beekeepers in Germany I think still read this book and of course trust the authority. The icon can’t be wrong, can he? I think this book is a big reason why this opinion keep coming up that it’s never been an enlarging of the cellsize.

Tobias Stever is a beekeeper that has covered the cellsize on his website with an article. His conclusion is that no enlargement has been done and therefore the regression down in size today is not natural. http://www.bienenarchiv.de/veroeffentlichungen/2003_zellengroesse/zellengroesse.htm

Historical measurements

This conclusion of Stever is contradicted by his own list of historical measurements of cellsizes. When you read his article and other articles on cellsizes it’s hard to find insight that different sizes in the hive mostly are used differently by the bees. And that the different sizes are often found in certain places on the comb and in the hive.

The cellsizes in a hive

T W Cowan (1890) in a book mentions that larger cells normally are found at the edges of the wax combs and smaller at the center. Today if you study a topbar hive (TBH) which has deep combs enough, you will see that largest worker cells are generally found at the top and furthest away from the entrance. That’s mainly where honey is stored and not where brood is reared. If such a hive is not started with large cell bees you will probably find 5.1 and smaller cell sizes closer to the bottom and the entrance.

A topbar comb with Dennis Murrel in Montana. Smallest cellsizes at the bottom close to the entrance. Biggest away from the entrance and at the top.

A topbar comb with Dennis Murrel in Montana. Smallest cellsizes at the bottom close to the entrance. Biggest away from the entrance and at the top.

Samples for measurement

So with all these measurements, where are the samples taken that are measured? And how many are they? Is the whole of the hive covered when samples are taken? Have the bees built the combs without the help of wax foundation? Is it a swarm from a large cell colony or is it a colony that has lived for some generations on combs built and rebuilt by themselves?

In some cases you are given the smallest and the largest cellsizes found, so there you know that more than one sample is taken, but also you rarely are presented with the number of samples taken and from where in the hive.

The conclusion is that you have to read the original books and articles where the figures are presented to see if you can find out how accurate the measurements are concerning how natural the cellsizes of these bees are.

Cowan

One good book in this respect is ”The Honey Bee-Its Natural History, Anatomy and Physiology”, Houlston & Sons (1890), T W Cowan, pages 179-181. The book can be read online here: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89094199411;view=1up;seq=10

Some literature

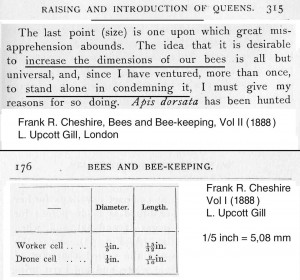

Thomas Wildman in England in his “A Treatise on the Management of Bees” (1770) gives 4.6 mm to 5.1 mm cellsize. T W Cowan in England in his ”The Honey Bee-Its Natural History, Anatomy and Physiology” (1890) gives 4.72 [1.86 inch/10cells – decimals!] to 5.36 mm [2.11 inch/10], page 181). Cowan also gave the average to be 1/5 of an inch ≈ 5.08 mm. That’s an easy figure – 5 cells to the inch (a common way of naming this size of wax foundation was 900 cells/dm2, which once was how wax foundation also was called, by how many cells/dm2 they gave). A I Root in USA adopted 5 cells to the inch for the first commercial wax foundation milling rollers in 1876.

Enlarging

Usmar Baudoux from Belgium in the late 19th century propagated for enlarging bees to get longer tongues in the bees and bigger honey crops. He thought 700 cells/dm2 was a good size (5.74 mm cellsize). He published a number of articles in the magazine Bee World in 1933-34 on the subject. H Gontarski published in 1935 his work on using large cellsize. He came to the conclusion that 5.8 mm cellsize was the upper limit. Bigger cellsize and the bee colony couldn’t grow in strength. Here we are talking about cellsizes for the brood.

An illustration in Bee World January 1934 by Baudoux showing the differenses of the sizes of worker bees born in different cellsizes. The biggest bee (no 1) born in 6.0 mm cell. The smallest (no 9) born in 4.7 mm.

An illustration in Bee World January 1934 by Baudoux showing the differenses of the sizes of worker bees born in different cellsizes. The biggest bee (no 1) born in 6.0 mm cell. The smallest (no 9) born in 4.7 mm.

All but Frank Cheshire in England worked for larger bees, he said in his classic book (two volumes) defending 5 cells to the inch. “Bees & bee-keeping : scientific and practical”, L Upcot Gill (1886-1888), Frank R. Cheshire, part 1, p 176, part 2, pages 315-318. It can be read online through this link: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005782980

Some text examples from the book of Frank Cheshire.

Some text examples from the book of Frank Cheshire.

What happened then?

The understanding why there was a difference in cellsizes even on the same comb seemed to be lacking. Different cellsizes are most often used for different purposes, brood in smallest, honey in the biggest.

New foundation was most often given to bees in the honey supers above the brood, where sizes normally are bigger than in the broodnest. Remember 5.1 mm cellsize (5 cells to the inch) was an average for all sizes of cells in the bee colony. Now these bees earlier born in smaller cells helping to draw smaller cellsizes correctly weren’t there, they were not born any longer with the arrival of wax foundation.

What size of the cells bees draw naturally depends a lot on

- how big the bees themselves are,

- on their genetics and

- the food they get. And the food is also dependent on the cellsize.

Sometimes this created problems for the bees to draw the foundation well enough, especially when the honeyflow was rich – the bees wanted honey storage cells.

The best place for drawing out small cells is below the broodnest, the next best in the middle of or at the sides of and close to the broodnest.

In Gleanings of Bee Culture, December 1938, the son of A I Root, E R Root, argued for two things,

1. that cellsize shouldn’t be smaller than 5.2 mm and

2. that cellsize shouldn’t be bigger than 5.2 mm.

The argument for not smaller was that the bees drew the 5.2 foundation better than 5.1.

The argument for not bigger was the same as Frank Cheshire in England used.

Cheshire strongly argued against enlargement as the bees would come out of tune with nature. But Cheshire argued to not enlarge from 5.1 mm.

Some newer measurements

Thomas Seeley’s measurements in Arnot forest in northeastern USA of feral bees are used sometimes as argument against small cells. His result is though 5.2 mm cellsize – in average. And you know what average means don’t you. Smaller cellsizes where the brood is and the biggest sizes where honey is stored. The inbetween sizes used for both when needed.

Tom Seeley gave a number of excellent talks on the London Honey Show in October 2011, which I listened to. One described in detail his work investigating feral bees in the Arnot forest.

Tom Seeley gave a number of excellent talks on the London Honey Show in October 2011, which I listened to. One described in detail his work investigating feral bees in the Arnot forest.

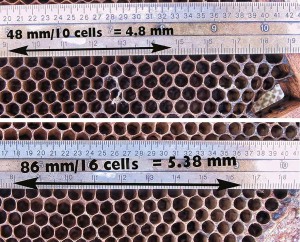

2002 Leif Hjalmarsson in southern Sweden took care of a colony from a widow that had lost her husband 10 years earlier. He had been a beekeeper with ten colonies. No one touched them after his death. It might have been a swarm that had entered one of the hives, or a surviver, that Leif took care of. Many combs were reworked by the bees. Evidently the cellsize of the foundation once used had been 5.4 mm. Now the cellsizes ranged between 4.77 and 5.4 mm.

A couple of the measurements from reworked comb from the colony Leif Hjalmarsson took care of.

A couple of the measurements from reworked comb from the colony Leif Hjalmarsson took care of.

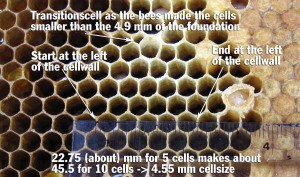

Myself I have measured down to 4.55 mm for sizes where my bees have had foundationless combs or similar. Quite common sizes were around 5.0 and sometimes up to 5.4 mm. I normally use 4.9 mm cellsize foundation in the broodnest. Most of my bees have no problems drawing 4.9 foundation well. After selection for varroa resistance they even draw 4.9 foundation well in the supers. A coincidence or a side effect? They winter well, give good honey crops and don’t swarm more than when I had them on large cells.

Here my bees didn’t follow the 4.9 pattern of the foundation when they rebuilt some cellwalls after I had taken them down for easier grafting larvae when queen rearing. Here they had drawn them 4.55 in the area rebuilt and the queen had layed eggs in the cells.

Here my bees didn’t follow the 4.9 pattern of the foundation when they rebuilt some cellwalls after I had taken them down for easier grafting larvae when queen rearing. Here they had drawn them 4.55 in the area rebuilt and the queen had layed eggs in the cells.

I like to think my small cell bees are more in tune with nature, more biologically optimized and therefore better armed for living a healthy life with little or no special help from me.

Hello Erik,

thank you for the good summary! I totally agree that the most important point is that there are different cellsizes in a hive and even on one comb.

Perhaps a first increase in cellsize has happened long before Baudoux. In Germany the first Foundation was made 1857 by Johannes Mehring with a cell-size of

5.55mm (“Die Tafel ist reiner Arbeitsbienenbau, 9 Zellen auf 5 Zentimeter” ). So why did he make such big cells? We have no evidence, that J. Mehring tried to increase the body-size, tongue-length, honey-stomach or anything else of the bee.

One idea could be, that when bees build natural comb in the very small frames, that were used at that time in Germany (ca. 23.5×18.3cm, or even smaller), bees mostly build honey-cells, because the broodnest naturally starts a little bit deeper, and so the measured cellsize would be the one of honey-cells (which then were used as brood-cells, because the bees had no other chance). I don’t know, what do you think?

Another interesting fact is, that Gontarski writes in 1937, when he experimented with different sizes of foundation, that the bees were able to build regular comb from foundation-cellsize down to 4.7mm without problems, which most of our recent bees are not able to.

Kind Regards

Ralf

Thanks Ralf for your comment. It was very interesting info about the tests Gontarski did and that the bees he used had no problems drawing 4.7 mm cellsize.

Concerning Mehring’s choice, we can only speculate why he choose the size he did. As almost all other measurements tends to show something else than that 5.5 mm should be a natural size for the broodnest, it’s natural to try to think about an explanation. First I would like to establish that the cellsize of his mold really was 5.5 mm. Could that be done? I guess it’s in a museum. I guess your quote in German indicates that.

Surely he did some kind of measurements of natural comb. It would have been interesting to know how many samples he measured, and from where in the nest he took them. If he measured natural comb in hollow tree or something. I didn’t know the frames were that small as you mention. He may well have measured on one or more of those (if he used them). In worst case he took only one piece of comb from only one colony far away from the broodnest, maybe easy to get at. Maybe he never thought about the possibility of different sizes. Yes, your speculation could be a possible explanation.

I really don’t like to comment again. However, the argumentory line is so beautiful, that I have to. I don’t know the history, but given nobody is hinting on different cell sizes within a naturall build comb so far, this is really a great throw. Besides it’s beauty to close the gap between different opinions, plus the provided supporting evidence the logic is appealing.